Genesis Story: Part I

The deep origins of life on earth

If you ever get the chance to travel back in time to the very early days of earth’s history, don’t. You certainly wouldn’t want to be there at its creation.

Our planet was born in a cataclysm four-and-a-half billion years ago, when a Mars-sized planet smashed into another huge lump of rock, our proto-earth. This collision released so much energy that the fledgling earth literally melted, and caused a huge molten glob of rock to be ejected into space, which cooled down to form the moon.

After this baptism of fire, the next five-hundred million years on earth were equally hellish. Red-hot magma flowed over the earth’s surface. Volcanic eruptions spewed out gases like hydrogen sulphide, methane, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen, creating an unbreathable atmosphere devoid of oxygen that would be toxic for much of life today. No oxygen also meant no protective ozone layer, so the young earth was bathed in fierce ultraviolet light.

As the planet cooled enough for molten rock to solidify into crust, conditions were still fiery. Oceans hot enough to poach an egg formed out of water delivered by comets and asteroids, as well as water vapour pulled in from space by earth’s gravity, and whatever water had been present in the cosmic dust out of which the earth formed. There’s still debate about whether oceans completely covered the planet, punctuated only by the tips of a few volcanoes, or whether there were more extensive regions of dry land early on.

Then, when the earth was about four-hundred million years old, it entered a three-hundred-million year cosmic storm known as the Late Heavy Bombardment Event, during which an abnormally high number of asteroids and comets were flying around the solar system.

Millennia after millennia, these space rocks rained down on earth – and our moon – smashing the surface to smithereens in explosions that would make nuclear bombs look like firecrackers, and filling the young atmosphere with immense clouds of debris and dust. The pock-marked, crater-ridden surface of the moon visible on a clear night provides vivid testimony of this violent period in our solar system’s youth.

Earliest life

It’s little wonder that geologists call the hellscape that existed on earth during its first half-a-billion years the Hadaen Eon after Hades, Greek god of the underworld. Not only was there no life in this chaotic, volatile world. Conditions were seemingly outright hostile to it.

And yet we know that life had evolved on earth by three-and-a-half billion years ago, within a billion years of earth’s creation. The evidence for this early life comes from fossilised stromatolites, layered structures created by bacteria which produce sticky compounds that cause sand and bits of rock to clump together into microbial mats that are laid one upon another over time to fashion dark, misshapen pods.

Stromatolites are still found today in places like Shark Bay in Australia. But these particular stromatolites are not billions of years old, and instead appear to have accumulated over the past couple of millennia.

It’s unlikely that the oldest stromatolite-based life found so far is actually the very first life on earth. That would be a bit too lucky. In any case, the kinds of bacteria that make stromatolites are complex organisms that must have evolved from earlier, simple organisms going back … well, who knows how long?

Indirect evidence from ancient minerals offers hints that life may have been present on earth 3.8 billion years ago, just after the Hadean Eon. And some genetic analyses have suggested that life had got going by 4.2 billion years ago, during the Hadean – though this estimate turns on a number of assumptions which may not hold true.

Maybe life could have sprung up in the Hadean if it wasn’t as hellish as implied by its name. Even the Late Heavy Bombardment Event may not have been that much of a threat to life had it existed then. Although many more asteroids and meteorites hit the earth during this period than strike us today, it’s not like huge rocks were smashing into our planet hour by hour, day by day. Major impacts would be separated by millions of years. It’s possible that when devastating impacts did occur, some life forms were safely tucked away and made it through to calmer times.

And even if conditions during the Hadean were inimical to life, it’s also possible that a bunch of interesting prebiotic chemistry happened at this point – chemistry that would create the raw materials that would begin to self-assemble into the first life soon after.

The bottom line is that we simply don’t know exactly when life arose, or what the precise geological conditions were when it did. Yet somewhere, somehow, at some point, something remarkable happened: lifeless chemistry crossed a threshold, and ushered in a new, complex, evolving world of living molecular biology.

Some people would argue this event was literally miraculous. Some, merely unlikely. Others, all but inevitable. Whatever the odds, it happened here, and it happened at least once. And with it the epic four-billion-year journey of life on earth had begun.

Getting back to our roots

A thorny problem sits at the heart of any account of the origin of life: no one knows how to define life itself. More than one hundred definitions have been offered, and while most capture at least some crucial facets of life, none bring them all together in a way everyone can agree on.

Life may be hard to define explicitly, but we seem to recognize it when we see it. A cell is clearly a living entity. A beaker of chemicals – even if they’re complex biological ones – is not. Separating them is a conceptually fuzzy zone, where the transition to life takes place.

If trying to define life is a fool’s errand, then maybe it’s easier just to live with a bit of fuzziness – which needn’t be a serious impediment to thinking about life’s origins in any case.

We can instead talk about a more clearly defined question: how did the first cell form? Cells are the smallest, most fundamental unit of life – even if we can’t say exactly what it is that makes them living. By recasting the origin of life question as the origin of cells, we can start focusing on key features that make a cell a cell.

One of these essential components is a border of some kind, a barrier between what’s within the cell, and what’s without. A boundary-defining membrane of some kind is a minimal requirement for defining a living organism as distinct from its non-living environment.

So even though it’s impossible to say what the first life might have been like in any detail, it was almost certainly a cell enclosed by a membrane. It would also have to meet certain other minimal requirements to qualify as life. This cell would need to extract energy from the world around it to survive and grow. It would need some way to obtain all the basic building blocks required to keep the biological machinery ticking over. It would need to be able to replicate. And, finally, it would have some sort of information-bearing system of heredity.

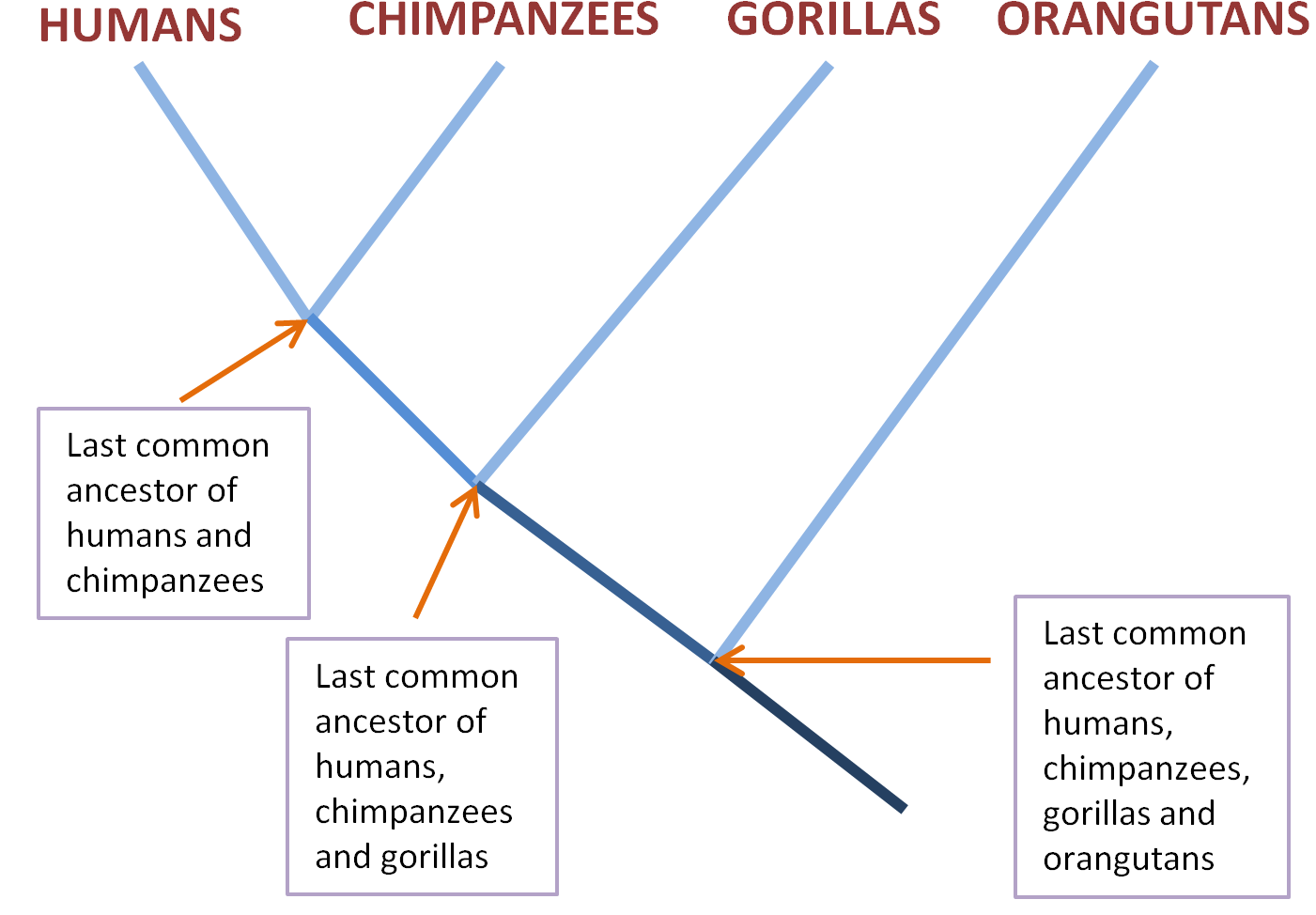

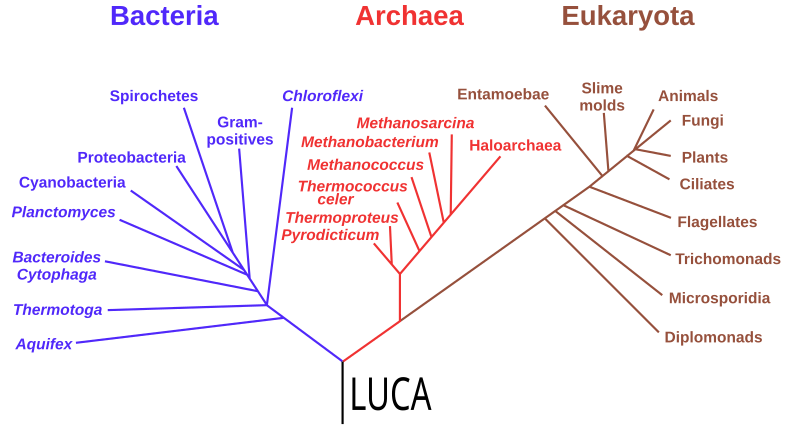

All this is present in what evolutionary biologists call the Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA), the species from which all life on earth today descends, the trunk of the tree of life. Imagine individual species living today are the tips of twigs in a dense tree top. To keep things simple, let’s focus in on our species and our closest relatives, chimpanzees and gorillas. These species, each represented by the tip of a twig, would be close together in the tree top.

If you trace a path down from a particular twig tip – from the human one, say – you’re going back in evolutionary time. Soon you’ll hit a junction, where the human twig merges with the one descending from the nearby chimpanzee tip. This junction represents the common ancestor of both chimpanzees and humans, and its twig descends until it merges with the gorilla line at the common ancestor of all three species.

The next junction gets us to the common ancestor of humans, chimpanzees, gorillas and orangutans. We can keep going, travelling further backwards in evolutionary time as species merge with each other into their ancestral species, until we get the ancestors of apes, then primates, then mammals, then animals, all the way back to the common ancestor of animals, plants and fungi, and even further back.

No matter which twig tip you start with, if you trace downwards and along the branches they coalesce with, and keep repeating the process, eventually you will hit the main trunk of the tree. When you get there, you’ve reached the common ancestor of all life on earth today, LUCA.

LUCA, however, is not a specific species that biologists can point to. The existence of LUCA is not a discovery, but an inference based on the evolutionary logic outlined above. As for when it may have lived, no one really knows, but some genetic analyses hint that it may have existed 4.2 billion years ago, in the Hadean Eon. Maybe it came a bit later. Roughly 4 billion years ago is a reasonable figure.

But even though no one can say what species it was, or when it emerged, it would have been a single-celled organism as it appears before any multi-cellular life. And it’s possible to infer some things about its biology following a simple logic: if there is some aspect of biology that is present in all species we know of, that’s likely because they all inherited it from LUCA – a more parsimonious explanation than the same feature evolving separately in every different species.

By looking at the biology of diverse species today, from bacteria and yeast to birds and bees, and seeing what’s common to them all, it’s reasonable to infer that LUCA’s biology was as complex as the cells of contemporary life. And that means that LUCA was almost certainly the product of millions of generations of evolutionary tinkering and refinement, and almost certainly not the very first life form, but the evolutionary descendant of earlier, simpler kinds of life, or maybe a single Ur-life form.

The first life would have been simpler, less efficient, less robust and generally jankier than LUCA, but it was probably built around the same basic biochemical ingredients, or something similar. Any origin-of-life story has to explain how simpler, less evolutionarily refined biochemistry and biology came about. Further, it has to explain how these ingredients came together and became assembled into connected networks that marked the shift from chemistry to biology.

Soupy beginnings

One of the most widely known ideas for the origin of life is the evocative notion of a primordial soup. Independently developed in the 1920s by the Russian biochemist Aleksandr Oparin and the British biologist JBS Haldane, the primordial soup theory proposed that the organic molecules of life could have formed out of simpler inorganic chemicals in warm water when stimulated by ultraviolet light or some other energy source.

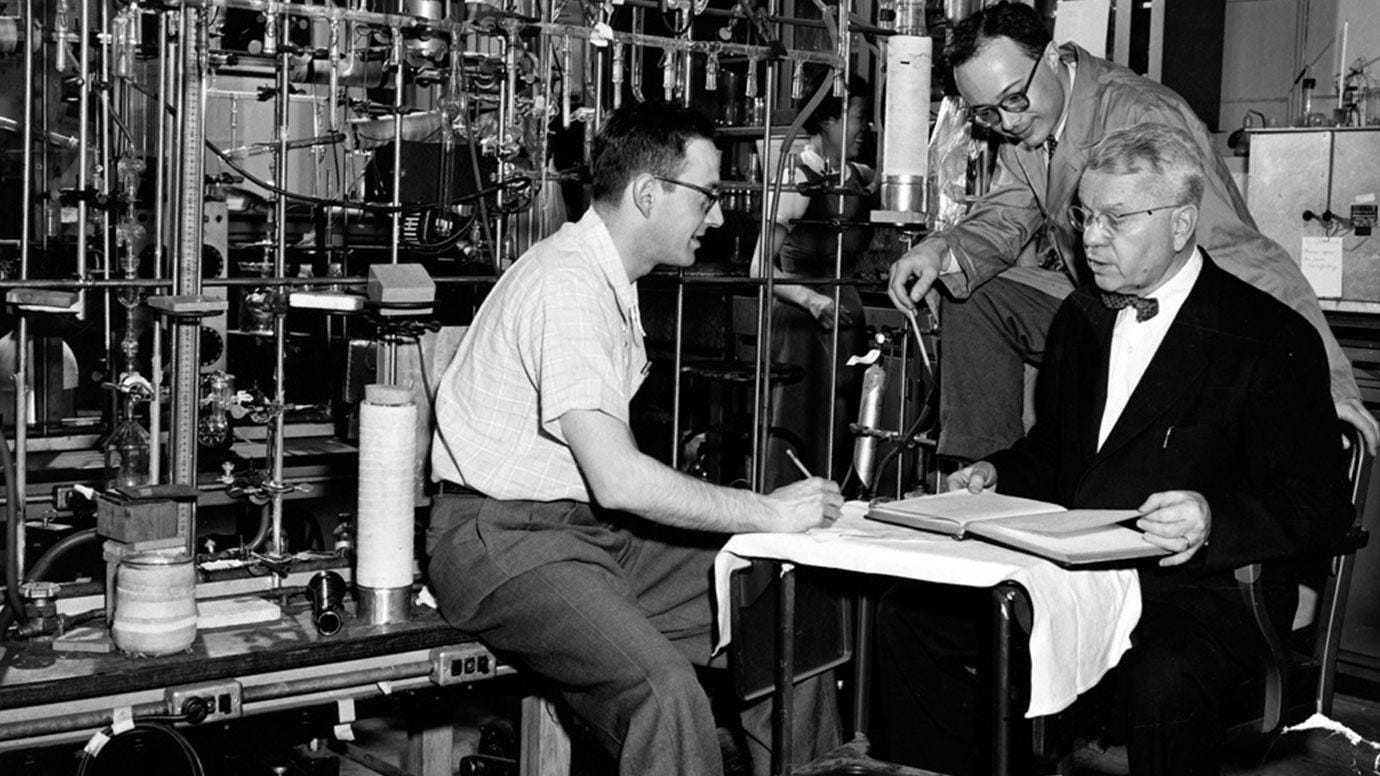

The idea floated around until 1952, when two Harvard chemists set out to find out how much you can really get out of a primordial soup. Stanley Miller, a young researcher at the beginning of his career, designed and ran the experiments, which were supervised by Harold Urey, who had won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1934 for his discovery of deuterium (also known as heavy hydrogen).

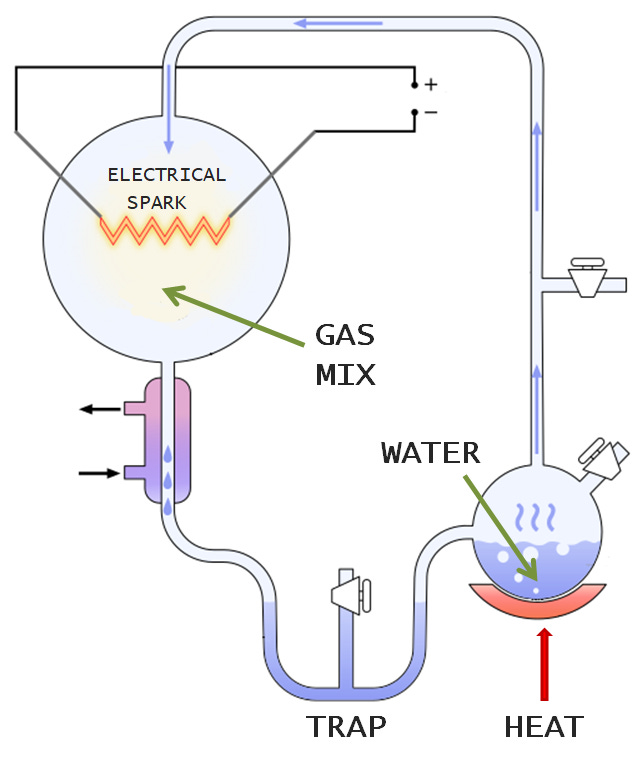

Miller and Urey’s experiments aimed to replicate the conditions of early earth in a relatively simple set up: round glass flasks connected by glass tubes into a closed loop, all of which could fit into the corner of your bedroom.

There were three crucial components of the Miller-Urey system. The first was a flask containing water, which represented the earth’s oceans. This water was heated from below, producing hot vapour that travelled up through a tube and round to a second flask filled with the gases methane, ammonia and hydrogen. This gaseous mixture, supposed to replicate the early atmosphere, was then zapped with electrical sparks, mimicking lightning, and pushed out of the mixing chamber and cooled until it condensed into a molecular soup that collected in a trap at the bottom of the apparatus.

After the experiment had run for a day, a yellowish liquid formed in the trap, and after six days had turned dark reddish-brown. When Miller extracted and analysed the dark, turbid broth, he found that it contained five of the twenty naturally occurring amino acids, the building blocks of proteins, one of life’s key kinds of molecules. It also contained a lot of other junk, including unusual amino acids not found in biology.

Showing you could get from simple inorganic chemistry to some of life’s essential building blocks was a big step forward, and would remain the most famous work Miller would ever do. It was also a huge stimulus for research into the origin of life.

Yet a few amino acids obviously does not add up to life. Nor is it sufficient for life to get off the ground. Over the coming decades, Miller tried out numerous variations of the original set up, especially as ideas changed about what starting ingredients were likely to have been available on early earth. Some were more successful than the first, and produced more amino acids, but fell far short of generating the full gamut of molecules needed for life – which were not deeply understood at that point anyway.

That was all to change. Just as Miller was publishing his work in 1953, the world of biology was on the cusp of a molecular revolution that would reveal how the basic mechanisms of life work at the atomic level. The biological world revealed in this revolution brought into stark relief the awesome challenge of explaining the chemistry-to-biology transition that made life possible.

Life gets more complex

During the years leading up to the Miller-Urey experiments, a growing number of biochemists began looking at what is today the most famous molecule in biology: DNA. Ever since the flourishing of genetics in the early twentieth century, scientists had tried to figure out the material basis of hereditary, the stuff genes are made from. By the mid-1940s, there was good reason to believe it was a kind of nucleic acid, specifically deoxyribose nucleic acid, or DNA.

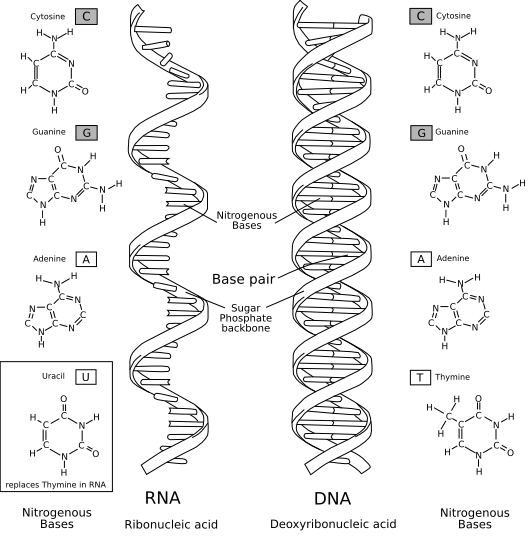

DNA was known to be made out of four different kinds of molecules called nucleotides, each customarily denoted by a single letter – adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G) and thymine (T). These nucleotides are very similar but differ in a key component called the base, so sometimes A, C, G and T are called nucleobases, or just bases. Other nucleic acids were also known to exist at the dawn of molecular biology. The most important was ribose nucleic acid, or RNA, which is made out of slight variants of DNA’s A, C and G nucleotides, and with T replaced with uracil (U).

What remained unknown in 1950 was how nucleotide subunits connected to form large DNA molecules, and how they could carry genetic information. X-ray crystallography, a technique developed in the 1910s to decipher the structure of molecules, had been applied to DNA in 1937, and revealed it to possess some kind of regular structure but provided no real detail.

By the early 1950s, higher-resolution images were available, but they were not straightforward to interpret. Linus Pauling, a Nobel-prize-winning scientist, believed they showed DNA to have a triple helix structure. He was wrong. James Watson and Francis Crick, inspired by exceptional X-ray images of DNA captured by Rosalind Franklin and her student Raymond Gosling, deduced the correct structure, the famous double helix.

In this elegant, winding staircase of a molecule, the nucleotides on one helical strand, jutting out like steps up a ladder, line up with and connect with nucleotides on the other strand, locking the two individual strands into the iconic double helix.

The connections between nucleotides – or, more precisely, between the bases of each nucleotide – follow very clearly defined rules: A pairs with T, and C with G. We now call this Watson-Crick-Franklin base pairing, and it means that given the sequence of one strand, you can immediately deduce the sequence of its complementary partner strand.

If the two strands are separated to expose unpaired nucleotides, then each strand could be used as a template for assembling a new, complementary strand. New nucleotides could be added to the copy strand according to the nucleotide pairing rules – A pairing with T, C pairing with G – until new, double-stranded copies of the original are created. This is in fact how it happens in cells.

The molecular details of DNA replication would be worked out over the coming years. In the meantime, there was another pressing question: how is the information embodied in the nucleotide sequence of DNA actually used by cells? DNA by itself isn’t capable of doing much. So it was thought to exert its effects indirectly, by carrying information required to manufacture the proteins that do most of the biochemical work in cells, like replicating DNA, catalyzing metabolic reactions, and providing structural support for the cell.

Some people thought that proteins assembled directly on DNA, with the amino-acid building blocks of proteins lining up according to the sequence of nucleotides in a stretch of DNA - what we call a gene. Then, in the mid-1950s, Francis Crick offered a bold alternative. Crick proposed that DNA does not directly guide the synthesis of proteins, but instead is used to make an intermediary strand of RNA, which does directly guide protein synthesis.

Crick turned out to be spot on. Subsequent research found that gene expression – the process of reading DNA to produce a protein – begins when a protein molecule called RNA polymerase attaches to the start of a gene in a stretch of DNA. RNA polymerase then unwinds the double-stranded helix to expose the individual strands, one of which is used as a template to manufacture a single-stranded molecule of RNA via Watson-Crick-Franklin base pairing.

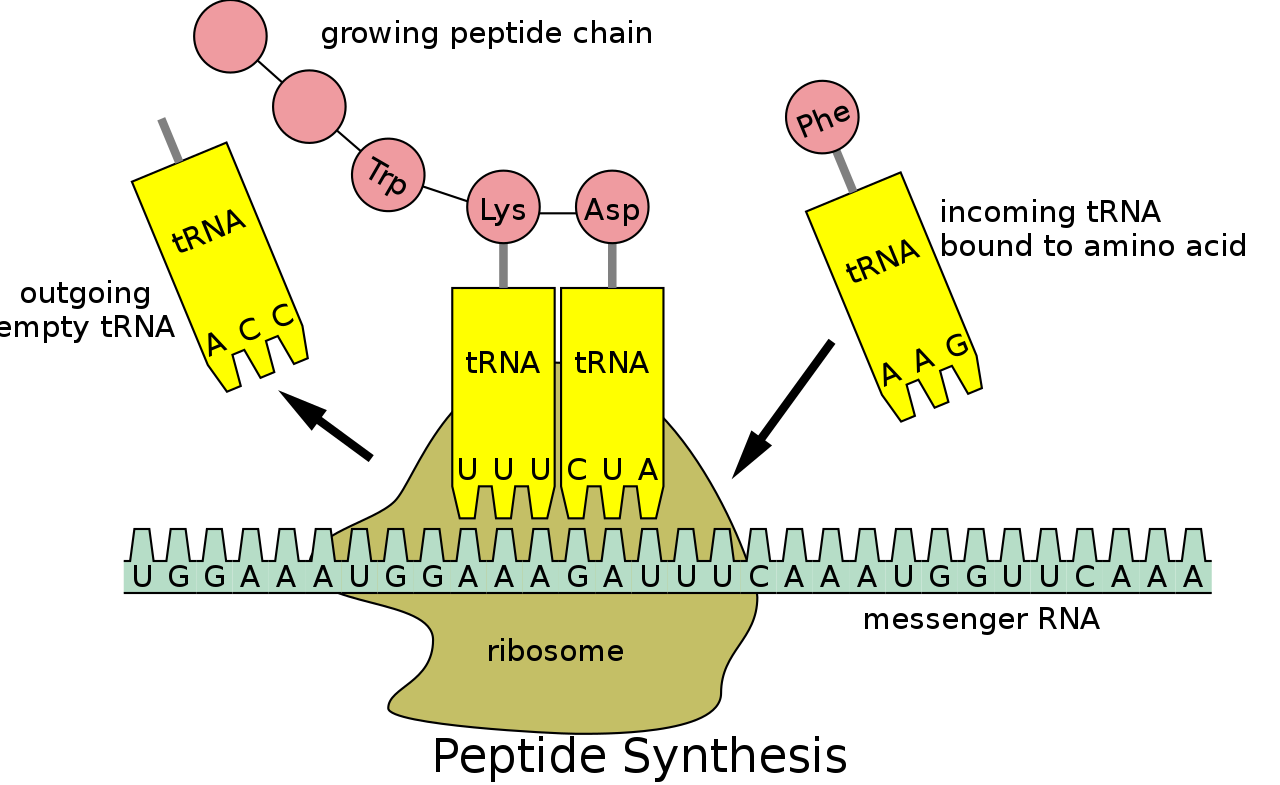

This RNA, called messenger RNA or mRNA, carries the information encoded in the gene out of the cell’s nucleus, where the DNA resides bundled into chromosomes. Once outside of the nucleus and in the main body of the cell, mRNA binds to a big protein structure called a ribosome. This complex structure uses the mRNA sequence as instructions to build a protein, adding one amino acid at a time based on the codons in the mRNA.

Even with the broad outlines of gene expression in place, biologists still faced a puzzle. There are at least two distinct biochemical languages spoken in the cell: the language of genes, written in just four nucleotides, and the language of proteins, written in twenty amino acids. That’s why molecular biologists call the process of creating a protein from mRNA translation, as the ribosome literally translates a message spelled out in nucleotides into a molecule written in amino acids. So what links these two languages? How does the genetic code work?

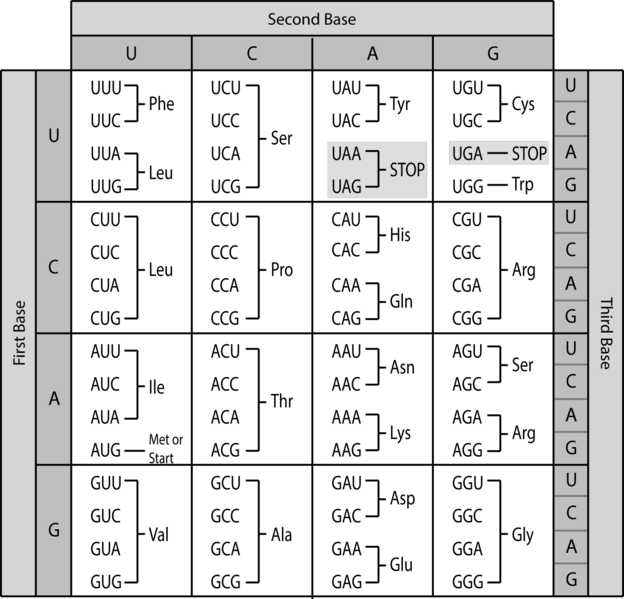

Once again, Crick’s fertile mind came up with an answer. In 1958, he envisioned a genetic code based on reading nucleotides in groups of three. If any of the four nucleotides could occupy the first, second or third position of a triplet, then simple math tells us that there are 43 or sixty-four possible triplets – more than enough to encode twenty amino acids.

Experimental work in the 1960s confirmed that nature does indeed use such a triplet genetic code, and deciphered which triplets, called codons, specified which amino acids should go in a protein. Molecular biologists could now draw up a simple chart showing how to translate between the language of genes and the language of proteins. (Technical aside: as T nucleotides in DNA are copied into U nucleotides in mRNA, and its mRNA that’s translated at the ribosome, the genetic code is actually spelled out with A, U, C, and G – no T.)

Armed with knowledge of the genetic code, the process of translation occurring at ribosomes can now be explained more fully. Warning: it’s fairly complicated. But it’s also astonishingly clever, and one of the central processes of life. It’s worth giving it a few moments. (There’s a short video linked after the description that makes all of this much more comprehensible.)

Recall that DNA is first used as a template to create mRNA, which then migrates out of the nucleus, where it is grabbed by a ribosome to be translated. Once attached to a ribosome, the mRNA is processed from one end to the other, with the ribosome shuffling the ribbon of mRNA through one codon at a time. As each codon is read, the amino acid it specifies is added to a growing chain.

To see how, we need to introduce another type of RNA called transfer RNA, or tRNA. The job of tRNA is to ferry amino acids to ribosomes and feed them into growing proteins. Each of the twenty kinds of amino acid attaches to a specific species of tRNA, which are differentiated by a triplet of nucleotides present in a loop that pokes out of all tRNAs. For example, tRNAs attached to valine have the triplet CAU in this loop. Those carrying glycine have GGC. And so on.

Returning to an mRNA being processed in a ribosome, suppose the codon being read is GUA, which codes for valine. Floating around the ribosome are various tRNAs and their amino-acid cargo, including tRNAs carrying valine with exposed CAU triplets. Watson-Crick-Franklin pairing rules make the GUA codon in mRNA complementary to the CAU ‘anticodon’ in tRNA. That means the codon and anticodon can line up with each other and pair up, holding the tRNA and its valine attachment in place.

Let’s say the next codon is CCG, encoding glycine. In floats a glycine-loaded tRNA bearing the complementary anticodon GGC, and attaches to the mRNA next the valine-carrying tRNA. This brings the two amino acids close enough together to be connected. With each codon read, another amino acid is added into the growing protein chain. After this has happened hundreds or thousands of times, a complete protein will have been produced.

Picturing how this complicated process plays out in the three-dimensional world of the cell is tricky, so I highly recommend taking less than three minutes to watch this video that shows it all from start to finish.

I vividly recall being utterly blown away when I first learned the intricate molecular details of gene expression and protein synthesis some thirty years ago. The logic of the system, and the mechanistic implementation of that logic, is so clever, so elegant, it will never cease to amaze me.

The revolution in molecular biology ushered in a new understanding and appreciation of life’s complexity, but it didn’t immediately offer any obvious answers to how life got started. If anything, the question of life’s origin looked harder than ever.

Not only were the molecules involved in the basic processes of life revealed in all their complexity, so too were the intricate webs of connections binding them into a cohesive, interdependent whole, in which genes encode proteins but a suite of specialized proteins are needed to decode those genes. Explaining the origin of life seemed even more daunting and intractable, the ultimate chicken-and-egg problem.

Life finds a way

For all of this biological order to have spontaneously sprung up out of early earth’s prebiotic geochemistry is more than just unlikely. To borrow a metaphor from the physicist Fred Hoyle, it would be like a hurricane blowing through a junkyard and assembling a Boeing 747. The only natural process capable of creating such organized, functional complexity is evolution by natural selection.

But how? And from what? The fact that the fundamentals of life, all present in LUCA, show clear signs of being evolved implies it was something simpler, but that doesn’t get us very far. And even a simplified, rougher version of modern life seems hard to get off the ground, as all the required elements appear so dependent on each other.

Yet life is here. Surely something must have come first and set the ball rolling. This first something would not have been life, but a crucial foothold for beginning the ascent out of lifeless chemistry and into a new world of living biology. So researchers working on the origin of life began wondering whether it was possible to get any of life’s key, complex biomolecules or proto-biological pathways out of prebiotic chemistry.

Some started with membranes and the creation of proto-cells. Others looked at protein-first worlds as the seed of life. For some, metabolism appeared the most promising starting point. And yet others explored the possibility that nucleic acids were the first recognizably biological molecules, around which the rest of biology emerged.

These are the origin stories we will explore in the next instalment. Subscribe so you don’t miss Part 2.

Very much enjoyed - both reading and listening. Indeed an amazing story ❤️